Sharks

Sharks

Sharks are a diverse group of cartilaginous fishes belonging to the subclass Elasmobranchii, which also includes rays and skates. With over 500 species identified, sharks have evolved over 400 million years, long before the dinosaurs roamed the Earth. Their evolutionary history spans multiple mass extinctions, showcasing their incredible adaptability and resilience. Sharks have been vital players in shaping marine ecosystems by acting as apex predators that maintain the balance of the food web, regulating the populations of other marine species to prevent overpopulation and ensure biodiversity.

Sharks are classified into several groups, including the well-known great white shark, tiger shark, hammerhead sharks, and the filter-feeding whale shark. While many sharks are apex predators, playing crucial roles in maintaining the health of ocean ecosystems, some species are filter feeders, consuming plankton and small fish.

Great White Shark (Carcharodon carcharias)

The Great White Shark is one of the most iconic and widely recognized apex predators in the world’s oceans. Known scientifically as Carcharodon carcharias, this species has captured human fascination for centuries due to its size, predatory capabilities, and role in marine ecosystems. Great Whites play a vital role as apex predators, controlling populations of marine mammals, fish, and other sharks, and thereby maintaining healthy oceanic food webs. Despite their reputation as dangerous to humans, interactions are rare, and these sharks are primarily threatened by human activities such as overfishing and habitat degradation.

Physical Characteristics

Adult Great Whites typically range from 4 to 5 meters (13–16 feet) in length, although exceptional individuals may exceed 6 meters (20 feet). Females are generally larger than males, weighing between 680–1,100 kilograms (1,500–2,400 pounds). Their robust, torpedo-shaped bodies are designed for efficient swimming and high-speed bursts, crucial for ambush predation. Their skin is covered in dermal denticles, which reduce drag and turbulence in the water. Countershading is a hallmark of this species: a gray dorsal side camouflages the shark from prey above, while a white ventral side makes it less visible from below. Great Whites have serrated, triangular teeth arranged in multiple rows, which are constantly replaced throughout life and are highly effective at slicing through flesh and bone. Their senses are finely tuned for predation, including acute vision, an exceptional sense of smell, the ability to detect electrical fields via the ampullae of Lorenzini, and a highly sensitive lateral line system to perceive vibrations in water.

Habitat and Global Distribution

Great White Sharks are found in temperate and subtropical coastal waters worldwide, including regions off North and South America, South Africa, Australia, and Japan. They are typically observed from surface waters down to 1,200 meters, utilizing both nearshore habitats and open ocean areas depending on life stage and food availability. Satellite tracking has revealed extensive long-distance migrations. Some individuals traverse thousands of kilometers across ocean basins, connecting nursery areas, feeding grounds, and mating sites. Sharks in South Africa and Australia exhibit seasonal migrations between seal colonies and offshore regions.

Diet and Hunting Behavior

Great Whites are generalist predators with a diet varying by age and location. Juveniles feed primarily on fish and rays, while adults consume marine mammals, large fish, and occasionally smaller sharks. These sharks employ stealth and speed to ambush prey, often approaching from below to capture seals near the surface. Spectacular breaching behavior has been documented in South Africa and California, where the shark propels its entire body out of the water during attacks. Great Whites can sustain high-speed bursts up to 25 km/h (15 mph), enabling effective predation of agile marine mammals. They are typically solitary but may aggregate around abundant food sources, and dominance hierarchies have been observed at seal colonies, where larger individuals have priority access to prey.

Reproduction and Life Cycle

Great Whites are ovoviviparous, meaning embryos develop inside eggs within the mother’s body and live young are born. Gestation is estimated to last 11–12 months. Females give birth to 2–10 pups per cycle, each measuring approximately 1.2–1.5 meters at birth. Juveniles inhabit shallow coastal areas, estuaries, and bays where predation risk is lower, gradually moving to deeper waters as they mature. Growth rates vary; individuals can live up to 70 years, though accurate age estimates rely on vertebral growth ring analysis.

Behavioral Ecology

Tagging studies indicate strong site fidelity to feeding areas, such as Seal Island (South Africa) and Farallon Islands (USA), while also showing long-distance migrations across open oceans. Observational studies and long-term tracking suggest problem-solving abilities, memory of prey locations, and strategic hunting techniques. Shark attacks on humans are rare and typically a case of mistaken identity. Great Whites often avoid humans, and research emphasizes education and precaution to reduce encounters. By selectively preying on sick, old, or weak individuals, Great Whites help regulate prey populations and contribute to ecosystem stability.

Conservation Status

Great Whites are listed as Vulnerable on the IUCN Red List. They are threatened by overfishing, including bycatch, finning, habitat degradation, and marine pollution. Coastal development impacts critical nursery areas. Global populations are declining, with some regional populations experiencing reductions over 50%. Conservation measures include protected marine areas, fisheries regulation, and bans on finning. Continued satellite tracking, population genetics studies, and monitoring of nursery grounds are essential for effective conservation strategies.

Scientific Observations

Breach hunting has been documented by divers and drone footage, showcasing high-speed surface attacks on seals. Stomach content analysis reveals seasonal and regional dietary shifts, reflecting prey availability. Satellite tagging demonstrates connectivity between nursery areas, feeding grounds, and mating regions across ocean basins. DNA studies reveal varying levels of genetic connectivity between populations, which is critical for conservation planning.

References

- Compagno, L. J. V., Dando, M., & Fowler, S. (2005). Sharks of the World. Princeton University Press.

- Domeier, M. L. (2012). Global Perspectives on the Biology and Life History of the White Shark. CRC Press.

- Werry, J. M., et al. (2012). Movement patterns of large predatory sharks. PLoS ONE.

- Goldman, K. J., & Musick, J. A. (2006). White Shark Biology and Conservation. Marine and Freshwater Research.

- IUCN Red List. Carcharodon carcharias.

Whale Shark (Rhincodon typus)

Physical Characteristics

Whale sharks are the largest living fish, reaching up to 18 meters (59 feet) and weighing as much as 20.6 tons. They have a broad, flattened head, wide mouth, and dark grey skin with pale spots and stripes unique to each individual.

Habitat and Distribution

Found in tropical and warm-temperate oceans worldwide, whale sharks are primarily pelagic, living in open water but diving to over 1,000 meters. They undertake long-distance migrations between feeding and breeding grounds.

Feeding Behavior

Whale sharks are filter feeders, using ram and suction feeding to consume plankton, small fish, copepods, krill, fish eggs, and small squid. They swim with mouths open, filtering water through gill rakers to capture prey.

Reproduction and Life Cycle

Whale sharks are ovoviviparous, with gestation lasting 12–16 months. Newborns measure 40–60 cm. Lifespan is estimated at 70–100 years, with some exceeding 130 years.

Behavior and Social Structure

Generally solitary, whale sharks aggregate at feeding sites or cleaning stations. They are docile and sometimes interact with humans, but should not be touched or ridden.

Conservation Status

Listed as Endangered by the IUCN. Threats include targeted fishing, bycatch, ship strikes, and habitat degradation. Populations have declined by ~50% over the past 75 years.

Scientific Observations

- Feeding: Surface feeding in high plankton areas, including coral reefs and upwelling zones.

- Migration: Satellite tagging shows long-distance movements between feeding and breeding areas.

- Aggregation Sites: Notable sites include Ningaloo Reef (Australia), Galápagos Islands, and Yucatán Peninsula (Mexico).

References

Thresher Shark (Alopias spp.)

Overview

Thresher sharks are instantly recognizable for their extraordinarily long, whip-like caudal fins, which can constitute up to half of their total body length. Adults typically range from 3 to 6 meters (10–20 feet), with some individuals exceeding 7 meters. They belong to the family Alopiidae and are pelagic predators, inhabiting open oceans but occasionally approaching coastal areas. Their evolutionary lineage dates back over 100 million years, making them one of the most ancient shark groups still extant today.

Feeding Behavior

Thresher sharks have a specialized hunting method called the tail-slap. Using the elongated upper lobe of their caudal fin, they stun or immobilize schools of small schooling fish such as sardines and mackerel. Field observations using underwater video recordings confirm this technique allows them to capture multiple prey simultaneously. They also occasionally feed on squid and small pelagic invertebrates.

Social Behavior and Migration

Thresher sharks are largely solitary but can aggregate in areas with high prey density. Tagging studies show they are capable of long-distance migrations, moving between tropical and temperate waters in search of food and suitable mating grounds.

Reproduction

Thresher sharks are ovoviviparous, meaning embryos develop within eggs inside the female before live birth. Litter sizes are small, typically 2–4 pups, and gestation may last up to 9 months. Slow growth, late sexual maturity, and low reproductive output make them particularly vulnerable to overfishing.

Conservation Status

Thresher sharks are listed as Vulnerable by the IUCN due to declining populations from targeted fishing and bycatch in tuna and swordfish fisheries. Conservation efforts include regional catch restrictions and improved monitoring of population trends.

Scientific References

Tiger Shark (Galeocerdo cuvier)

Overview

Tiger sharks are large apex predators, reaching lengths of 4 to 5.5 meters (13–18 feet) and occasionally exceeding 6 meters. Juveniles have distinctive vertical stripes that fade with age. These sharks occupy tropical and subtropical waters worldwide, frequently found near coral reefs, seagrass beds, and estuaries. Their adaptability in habitat selection and dietary diversity allows them to occupy a broad ecological niche.

Diet and Feeding Behavior

Tiger sharks have an opportunistic and highly varied diet. They feed on fish, cephalopods, seabirds, turtles, marine mammals, and even human-made debris, earning them the nickname “the ocean’s garbage can.” Smaller individuals mainly consume reef-associated fish and invertebrates, while larger adults take on turtles, rays, and carrion. Their robust jaws and serrated teeth allow them to crush shells and bones efficiently.

Social Behavior and Movement

Tiger sharks are generally solitary but can tolerate conspecifics in high-prey areas. Satellite tagging and acoustic telemetry reveal complex movement patterns, including seasonal migrations to reproductive and feeding hotspots. Some individuals show site fidelity, returning annually to specific coastal areas.

Reproduction

Tiger sharks are viviparous, giving live birth after internal gestation of 13–16 months. Litters contain 10–80 pups depending on the female. Newborns are independent immediately, facing high predation but benefiting from rich feeding grounds.

Conservation Status

The IUCN classifies tiger sharks as Near Threatened. They face pressure from targeted fisheries, shark nets, and habitat degradation. Despite these threats, they play a critical role in regulating prey populations and maintaining balance in coastal and pelagic ecosystems.

Scientific References

- Meyer, C. G., Papastamatiou, Y. P., & Holland, K. N., 2010. Quantifying the movement patterns and habitat use of tiger sharks. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 402, 223–236.

- Lowe, C. G., et al., 1996. Ontogenetic dietary shifts and feeding behavior of the tiger shark. Environmental Biology of Fishes, 47(3), 203–211.

Lemon Shark (Negaprion brevirostris)

Overview

Lemon sharks are medium-sized coastal sharks, typically measuring 2.4–3.5 meters (8–11 feet). Their yellow-brown coloration camouflages them against sandy bottoms. They inhabit warm, shallow coastal waters of the western Atlantic (New Jersey to Brazil) and eastern Pacific (southern Baja California to Ecuador), often using mangroves and coral reefs as nursery grounds.

Diet and Feeding Behavior

Lemon sharks feed mainly on bony fishes, crustaceans, and occasionally mollusks. Juveniles prefer structurally complex areas for protection while learning to hunt. Adults expand their diet to larger fish and sometimes seabirds. They are active predators, using stealth and burst swimming.

Social Behavior

Lemon sharks display notable social behavior. Individuals form stable associations, recognize familiar conspecifics, and often return to the same groups. This suggests advanced cognitive abilities uncommon among sharks.

Reproduction

Lemon sharks are viviparous, with gestation lasting 10–12 months. Females give birth in shallow nurseries, producing 4–17 pups per litter. Juveniles remain in nurseries for several months before moving to deeper waters.

Conservation Status

While not heavily targeted commercially, lemon sharks are vulnerable to habitat loss, especially mangrove deforestation. They are listed as Near Threatened by the IUCN.

Scientific References

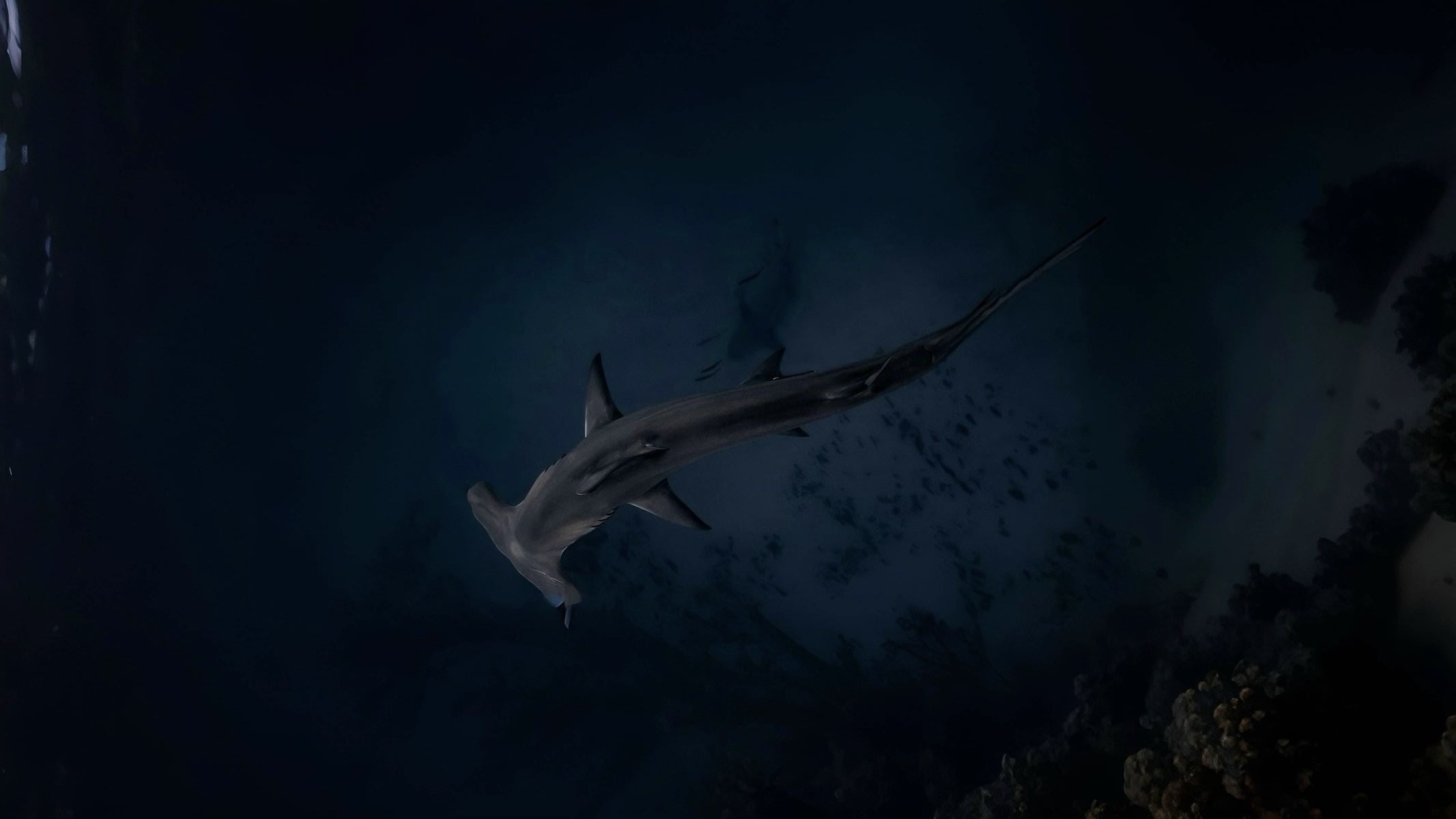

Hammerhead Shark (Sphyrnidae family)

Physical Characteristics

Hammerhead sharks have a distinctive “hammer-shaped” head (cephalofoil) that enhances vision, electroreception, and prey detection. Sizes range from 3–4 m for Scalloped Hammerheads to over 6 m for Great Hammerheads. They have streamlined, grayish-brown bodies and well-developed sensory systems, including ampullae of Lorenzini.

Habitat and Distribution

Distributed in tropical and warm-temperate oceans worldwide. Juveniles prefer shallow coastal areas, while adults migrate across deep offshore waters. Some species form large schools during the day and disperse at night for feeding.

Feeding Behavior and Diet

Feed on bony fish, cephalopods, crustaceans, and rays. Scalloped Hammerheads hunt stingrays using their wide heads to pin prey. They may hunt in groups and use electroreception to locate buried prey. Mostly active at dawn and dusk.

Reproduction

Viviparous, with gestation of 8–12 months. Litter sizes: 12–40 pups for Scalloped, 20–30 for Great Hammerheads. Newborns are independent and stay in shallow nurseries.

Social Structure and Behavior

Some species form large schools for protection and mating. Observations show problem-solving skills, coordinated hunting, and memory for prey. Seasonal migrations connect feeding, breeding, and nursery areas.

Conservation Status

Most species are Vulnerable or Endangered (IUCN). Threats include overfishing for fins, bycatch, and habitat degradation. Populations of Scalloped and Great Hammerheads have declined over 50%.

Scientific Observations

- Cephalofoil enhances detection of buried prey.

- Large schools observed for protection and mating (Hawaii, Galápagos).

- Satellite tracking shows long-distance seasonal migrations.

- Generally non-aggressive to humans, but caution near feeding sites.

References

Conclusion

Sharks are vital apex predators with evolutionary histories that showcase remarkable adaptations to marine life. Their conservation is critical due to threats like overfishing and habitat loss. Continued research using tracking technologies, genetic studies, and behavioral observations is essential to safeguard shark populations and maintain ocean ecosystem balance.

Whales

Whales are among the most fascinating and largest mammals inhabiting our oceans. As members of the order Cetacea, whales are fully adapted to marine life, having evolved from terrestrial ancestors around 50 million years ago. This evolutionary journey has given rise to a wide diversity of species with unique adaptations allowing them to thrive in different marine environments worldwide.

Whales are broadly categorized into two groups: baleen whales (Mysticeti) and toothed whales (Odontoceti). Baleen whales, such as blue whales and humpbacks, filter-feed by straining small prey like krill through plates of baleen in their mouths. Toothed whales, including sperm whales and dolphins, possess teeth and actively hunt larger prey such as fish, squid, and occasionally other marine mammals.

Blue Whale (Balaenoptera musculus)

The Blue Whale is the largest known animal to have ever existed on our planet, reaching lengths of up to 30 meters and weights of over 180,000 kilograms. This colossal marine mammal is a baleen whale, feeding primarily on krill and small fish, and plays a crucial role in maintaining healthy ocean ecosystems. Despite their massive size, Blue Whales are gentle filter-feeders and are not a threat to humans. However, human activities, such as whaling, shipping traffic, and ocean noise pollution, have historically caused dramatic population declines.

Physical Characteristics

Blue Whales are distinguished by their enormous size, long streamlined bodies, and bluish-grey skin with lighter mottling. They have a broad, flat head and small dorsal fin located far back on their bodies. Their mouths contain baleen plates instead of teeth, which they use to filter vast quantities of krill from seawater. Adults can weigh between 100,000 and 180,000 kilograms, and their tongues alone can weigh as much as an elephant. Their hearts are also massive, weighing approximately 450 kilograms, supporting the circulation of oxygen throughout their enormous bodies.

Habitat and Distribution

Blue Whales inhabit all the world’s oceans, primarily preferring deep offshore waters. They are highly migratory, spending summers in polar feeding grounds rich in krill and migrating to tropical and subtropical waters during winter for breeding and calving. Observations show that different populations, such as those in the North Atlantic, North Pacific, and Southern Ocean, have distinct migration patterns and feeding behaviors.

Feeding Behavior

Blue Whales are filter feeders, consuming up to 4 tons of krill per day during peak feeding season. They use a lunge-feeding technique, accelerating toward a dense krill patch with their mouths open and engulfing huge volumes of water. Once the water is expelled through their baleen plates, the krill remain trapped, ready to be swallowed. Observations from whale-watching expeditions and tagging studies have documented the efficiency and precision of this feeding strategy. Blue Whales generally feed alone or in loose aggregations and rely on their acute hearing to locate prey swarms.

Reproduction and Life Cycle

Blue Whales have slow reproductive rates, contributing to their vulnerability. Females reach sexual maturity around 5–10 years of age, while males mature slightly earlier. The gestation period is approximately 10–12 months, after which a single calf is born, measuring around 7 meters in length and weighing up to 2,000 kilograms. Mothers nurse calves for 6–7 months, providing rich milk that supports rapid growth of up to 90 kilograms per day. Calves remain with their mothers for up to a year, learning migratory routes and foraging behaviors.

Behavior and Social Structure

Blue Whales are generally solitary or found in small groups. They communicate using low-frequency vocalizations that can travel hundreds of kilometers, especially in deep ocean waters. These vocalizations are used in mating displays, navigation, and possibly coordinating feeding. Recent acoustic monitoring studies reveal that these calls vary regionally and seasonally, indicating complex social and migratory behaviors.

Conservation Status

Historically, commercial whaling in the 20th century caused catastrophic declines in Blue Whale populations. Since the international ban on whaling, populations have slowly recovered, but Blue Whales are still classified as Endangered by the IUCN. Current threats include ship strikes, entanglement in fishing gear, ocean noise pollution, and the effects of climate change on krill availability. Long-term satellite tagging and photographic identification studies help scientists monitor populations and develop conservation strategies.

Scientific Observations

Satellite tagging reveals extensive migrations across entire ocean basins, demonstrating high mobility and site fidelity to feeding areas. Acoustic research shows that vocalizations can carry up to 1,000 kilometers underwater, allowing communication between widely separated individuals. Stomach content and fecal analyses provide detailed information on diet composition and seasonal feeding habits. Observational studies from whale-watching expeditions document social behaviors, surface breathing patterns, and feeding techniques.

References

- Branch, T. A., et al. (2007). Past and present distribution, densities, and movements of blue whales across the Southern Hemisphere. Science.

- Goldbogen, J. A., et al. (2006). Kinematics of foraging dives in fin and blue whales. Journal of Experimental Biology.

- IUCN Red List. Balaenoptera musculus.

- Nowacek, D. P., et al. (2004). North Atlantic right whales ignore ships but respond to alerting signals. Biology Letters.

- Redfern, J. V., et al. (2006). Techniques for cetacean–habitat modeling. Marine Ecology Progress Series.

Humpback Whale (Megaptera novaeangliae)

The Humpback Whale is a large baleen whale species renowned for its complex vocalizations, acrobatic displays, and long migrations. Adults reach lengths of 12–16 meters and weights up to 36,000 kilograms. Humpback Whales feed primarily on small fish and krill and play a significant role in marine ecosystems by influencing prey populations and nutrient cycling. Their complex behaviors and vocalizations have fascinated scientists and the public alike, making them one of the most studied cetaceans in the world.

Humpbacks are divided into multiple regional populations, each exhibiting unique migration patterns, breeding behaviors, and feeding strategies. These subpopulations are often geographically and genetically distinct, reflecting adaptations to their specific oceanic environments. Understanding these populations is critical for effective conservation management and highlights the ecological diversity within the species.

Physical Characteristics

Humpback Whales are distinguished by their long pectoral fins, which can span up to one-third of their body length, and unique dorsal humps. Their bodies are robust, with distinctive knobby protuberances (tubercles) on their heads and jaws. Humpbacks have dark dorsal coloration with varying patterns on the ventral side of their flukes, which are used for individual identification in research studies. Their baleen plates, numbering 270–400 per side, allow them to filter-feed efficiently.

Habitat and Distribution

Humpback Whales are cosmopolitan, found in all major oceans. They occupy coastal and offshore waters, often preferring continental shelf areas during feeding season and tropical or subtropical waters for breeding. Humpbacks undertake some of the longest migrations of any mammal, traveling up to 25,000 kilometers annually between high-latitude feeding grounds and low-latitude breeding grounds.

Feeding Behavior

Humpbacks use diverse feeding strategies, including bubble-net feeding, lunge feeding, and solo surface feeding. Bubble-net feeding involves cooperative hunting, where whales create a circle of bubbles to herd and concentrate prey such as krill or small schooling fish. This cooperative behavior, often involving multiple individuals, demonstrates social complexity rarely observed in large marine mammals. Humpbacks are primarily filter feeders, engulfing large volumes of water and prey before expelling the water through baleen plates.

Reproduction and Life Cycle

Humpbacks reach sexual maturity around 4–5 years of age. Females give birth every 2–3 years after an 11–12 month gestation period. Calves are born in tropical or subtropical waters, measuring approximately 4–5 meters in length and weighing up to 1,000 kilograms. Calves nurse for 6–10 months, gaining 45 kilograms per day, and often accompany their mothers on extensive migrations. Juveniles gradually transition from shallow coastal areas to deeper ocean habitats as they mature.

Behavior and Vocalizations

Humpbacks are famous for their complex songs, sequences of repeating vocalizations primarily produced by males during the breeding season. These songs can last up to 20 minutes and are transmitted over long distances underwater. Acoustic research suggests songs may play roles in mate attraction and male-male competition. Humpbacks also exhibit acrobatic behaviors such as breaching, tail slapping, and pectoral fin slapping, which may function in communication, play, or parasite removal. Observations from whale-watching tours and research expeditions document these behaviors frequently.

Subpopulations and Regional Behaviors

North Pacific Population: These whales migrate between feeding grounds in the Gulf of Alaska and Bering Sea to breeding grounds near Hawaii, Mexico, and the Philippines. They primarily feed on krill, herring, and sand lance, often using cooperative bubble-net feeding. Breeding occurs in Hawaiian waters, with males producing complex songs and engaging in competitive displays.

North Atlantic Population: They migrate between feeding areas in the Gulf of Maine, Newfoundland, Iceland, and Norway to breeding grounds in the Caribbean. They feed heavily on small schooling fish and krill, often using lunge-feeding techniques. Males sing structured, seasonally changing songs, and maternal care is observed in shallow waters.

Southern Hemisphere Population: Southern Hemisphere Humpbacks migrate between Antarctic feeding grounds and tropical breeding areas near Australia, New Zealand, Brazil, and Madagascar, traveling over 8,000 kilometers each way. In Antarctic waters, they feed almost exclusively on krill using coordinated movements. Calving occurs in low-latitude tropical waters, and social structures include mother-calf pairs and temporary aggregations during mating.

Conservation Status

Once heavily targeted by commercial whaling, Humpback Whales were brought to the brink of extinction in many regions. Since the international ban on commercial whaling, populations have rebounded, although they remain vulnerable to ship strikes, entanglement in fishing gear, and climate-induced changes in prey distribution. While the IUCN lists the global population as Least Concern, certain regional populations remain endangered. Understanding subpopulations is critical for targeted conservation strategies, such as mitigating ship traffic in breeding areas and monitoring prey availability in feeding grounds.

Scientific Observations

Migration Fidelity: Individual Humpbacks consistently return to the same feeding and breeding areas each year.

Cultural Transmission of Songs: Songs vary regionally, with evidence of cultural transmission across populations.

Feeding Innovation: Certain populations display cooperative bubble-net feeding, while others adapt to local prey availability.

Population Connectivity: Genetic analyses indicate occasional mixing between subpopulations, though most groups remain largely separate.

References

- Clapham, P. J., & Mead, J. G. (1999). Megaptera novaeangliae. Mammalian Species, 604, 1–9.

- Cartwright, R., Waugh, S. M., & Baker, C. S. (2012). Migratory connectivity of Southern Hemisphere Humpback Whales. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 458, 259–272.

- Mobley, J. R., Herman, L. M., & Reilly, S. B. (2000). Humpback Whale Population Monitoring in Hawaiian Waters. Marine Mammal Science, 16(1), 1–25.

- Baker, C. S., Palumbi, S. R., Lambertsen, R. H., et al. (1993). Population structure of nuclear and mitochondrial DNA variation in North Pacific Humpback Whales. Marine Mammal Science, 9(3), 290–300.

- IUCN Red List. Megaptera novaeangliae.

- Tyack, P. L., & Clark, C. W. (2000). Communication and acoustic behavior of cetaceans. In Cetacean Societies: Field Studies of Dolphins and Whales.

- Nowacek, D. P., Johnson, M. P., & Tyack, P. L. (2001). North Atlantic Humpback Whale feeding and social behavior. Marine Mammal Science, 17(2), 397–419.

Sperm Whale (Physeter macrocephalus)

Sperm Whale (Physeter macrocephalus)

Sperm Whales are the largest toothed whales and one of the most iconic deep-diving marine mammals. Adult males can reach lengths of up to 20 meters and weigh over 57,000 kilograms, making them the largest toothed predator on Earth. Females are smaller, averaging 11–14 meters in length. Their massive heads house the spermaceti organ, which plays a critical role in echolocation and buoyancy control during deep dives. Sperm Whales primarily feed on squid but also consume deep-sea fish and other cephalopods. They are highly social, displaying complex behaviors, communication, and family structures that fascinate researchers worldwide.

Physical Characteristics

Sperm Whales have robust, cylindrical bodies with a characteristic large square-shaped head, comprising about one-third of their total body length. Their skin is usually dark gray, sometimes marked with scars from squid beaks or social interactions. Unlike baleen whales, Sperm Whales possess conical teeth only in their lower jaw, which fit into sockets in the upper jaw. These teeth are used to grasp large prey during deep dives.

Habitat and Distribution

Sperm Whales are cosmopolitan, inhabiting deep offshore waters across tropical, temperate, and polar regions. They prefer waters deeper than 1,000 meters where their primary prey, giant squid and other deep-sea organisms, reside. The species exhibits strong sexual segregation: adult males tend to inhabit higher-latitude offshore waters, while females and calves stay in lower-latitude, warmer areas for social cohesion and calf protection.

Feeding Behavior and Deep Diving

Sperm Whales are renowned for their deep-diving abilities, regularly reaching depths of 500–2,000 meters, and in some cases, exceeding 3,000 meters. They can remain submerged for over 90 minutes. Echolocation, facilitated by the spermaceti organ, allows them to navigate and detect prey in complete darkness. Their diet consists predominantly of squid, including the elusive giant squid (Architeuthis dux), but also includes deep-sea fish. Observational studies and tagging data have revealed complex hunting strategies, including cooperative foraging among females and juveniles in pods.

Social Structure and Communication

Females and calves form matrilineal social units of 10–20 individuals, while adult males often lead more solitary lives or form temporary bachelor groups. Sperm Whales exhibit one of the most sophisticated vocal communication systems among marine mammals. They produce series of clicks, known as “codas,” which are used for individual identification, coordination, and potentially cultural transmission of behaviors. Long-term field observations have documented mother-calf interactions, alloparental care, and social learning, demonstrating their cognitive complexity.

Reproduction and Life Cycle

Sexual maturity in females occurs around 8–13 years, while males mature at 18–21 years. Gestation lasts approximately 14–16 months, with females typically giving birth to a single calf. Calves are nursed for over two years, during which they learn essential survival skills. Life expectancy ranges from 60 to 70 years, and sperm whales are considered one of the longest-living toothed whale species.

Conservation Status

Historically, sperm whales were heavily targeted by whalers for spermaceti oil and ambergris. Populations were severely depleted during the 18th–20th centuries, but commercial whaling has ceased, and some populations show signs of recovery. Modern threats include ship strikes, entanglement in fishing gear, noise pollution affecting echolocation, and climate-induced changes in deep-sea prey availability. The IUCN currently lists the global population as Vulnerable.

Regional Populations and Observations

- North Atlantic Population: Often studied around the Azores, this population displays strong matrilineal social structures. Codas vary among pods, suggesting regional dialects.

- Southern Ocean Population: These whales frequent the deep waters surrounding Antarctica, diving to hunt squid under ice-covered regions.

- Pacific Population: Observations near New Zealand and the Philippines show female-led pods with complex social networks and evidence of intergenerational knowledge transfer.

Scientific Observations

- Echolocation: High-frequency clicks enable detection of prey at extreme depths, demonstrated through tagging studies.

- Social Learning: Calves learn hunting and social behaviors from older females in the pod.

- Deep Diving Adaptations: Anatomical features such as flexible ribcages and specialized oxygen storage allow prolonged dives.

- Human Interaction: Though rarely aggressive, sperm whales are sensitive to noise pollution from ships and sonar, affecting their communication and diving behavior.

References

- Whitehead, H. (2003). Sperm Whales: Social Evolution in the Ocean. University of Chicago Press.

- Teloni, V., Johnson, M., Miller, P., & Madsen, P. T. (2008). Shallow food for deep divers: Dynamic foraging behavior of male sperm whales in the Mediterranean. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 370, 75–89.

- Gero, S., Whitehead, H., & Rendell, L. (2016). Individualized social preferences and long-term social fidelity in sperm whales. Animal Behaviour, 113, 265–272.

- IUCN Red List. Physeter macrocephalus.

- Madsen, P. T., Wahlberg, M., & Møhl, B. (2002). Male sperm whale behavior during deep foraging dives. Journal of Experimental Biology, 205, 1899–1906.

Bowhead Whale (Balaena mysticetus)

Bowhead Whale (Balaena mysticetus)

Bowhead Whales are large baleen whales uniquely adapted to life in the Arctic and sub-Arctic regions. Adults can reach lengths of 14–20 meters and weigh up to 100,000 kilograms, making them among the heaviest animals on Earth. They are notable for their enormous bow-shaped heads, which make up about one-third of their body length, and their massive baleen plates used to filter tiny prey from Arctic waters. Bowhead Whales are long-lived, with some individuals estimated to live over 200 years, making them one of the longest-living mammals known.

Physical Characteristics

Bowheads have robust, rotund bodies with a thick layer of blubber, often exceeding 50 centimeters, which insulates them from frigid Arctic waters. Their heads are broad and arched, allowing them to break through sea ice up to 60 centimeters thick. They possess the longest baleen plates of any whale, reaching over 4 meters, enabling them to efficiently filter copepods, krill, and other small invertebrates from the water. Their skin is dark with occasional white patches, and they often display scars from interactions with other whales, predators, or ice.

Habitat and Distribution

Bowhead Whales inhabit Arctic and sub-Arctic waters, primarily within the Chukchi, Beaufort, Bering, and Greenland Seas. They are highly adapted to living in ice-covered regions, often navigating through leads and polynyas—openings in the ice—to feed and breathe. Seasonal movements include migration between wintering and summering areas, generally moving north in summer to feed and south in winter for breeding.

Feeding Behavior

Bowhead Whales are filter feeders, using their enormous baleen plates to strain small crustaceans, zooplankton, and copepods from dense Arctic waters. They typically feed in groups, swimming slowly with mouths open to maximize prey intake. Observations from tagging studies and icebreaker-supported expeditions reveal that bowheads can remain at depth for up to 30 minutes while foraging, demonstrating remarkable adaptations to cold, low-light environments.

Reproduction and Life Cycle

Females reach sexual maturity around 10 years of age, while males mature slightly earlier. Gestation lasts approximately 13–14 months, and calves are born during the winter in ice-free or lightly iced waters, measuring about 4–5 meters and weighing 1,000 kilograms. Calves nurse for up to a year, growing rapidly in the rich, high-latitude waters. Long-term studies indicate strong maternal care, with calves staying close to their mothers during their first year.

Social Structure and Vocalizations

Bowhead Whales are social and vocal animals, often found in small groups of 2–5 individuals, although larger aggregations occur in feeding and migratory areas. They produce a wide variety of calls, including moans, chirps, and complex songs, primarily during the breeding season. These vocalizations are believed to play roles in mate attraction, social cohesion, and navigation under ice. Recent research using hydrophone arrays has revealed that bowheads have highly individualistic vocal signatures and may even exhibit cultural transmission of song patterns across populations.

Conservation Status

Historically, Bowhead Whales were extensively hunted by commercial whalers for blubber and baleen, causing severe population declines. Since the implementation of hunting bans and strict management in the 20th century, populations have shown substantial recovery. Current estimates suggest tens of thousands of individuals globally. Nevertheless, bowheads remain vulnerable to ship strikes, entanglement in fishing gear, climate change affecting ice coverage and prey distribution, and noise pollution from shipping and seismic surveys. The IUCN currently lists Bowhead Whales as Least Concern, though some regional populations, such as the Okhotsk Sea stock, are considered Endangered.

Scientific Observations

- Ice Navigation: Bowheads have been observed breaking through sea ice up to 60 cm thick to breathe, showing unique morphological and behavioral adaptations.

- Longevity: Analysis of eye lens amino acids and baleen growth layers indicate lifespans over 200 years for some individuals.

- Migration: Tagging studies reveal precise migratory routes between summer feeding areas and winter breeding grounds.

- Vocal Complexity: Acoustic monitoring shows that bowheads have some of the most complex and variable vocalizations among baleen whales, possibly used for social learning and mate selection.

References

- George, J. C., et al. (1999). Age and growth estimates of bowhead whales (Balaena mysticetus) via aspartic acid racemization. Canadian Journal of Zoology, 77(4), 571–580.

- Koski, W. R., Miller, G. W., & Zeh, J. E. (2006). Bowhead whale biology and ecology in the Arctic. Marine Mammal Science, 22(3), 539–573.

- Moore, S. E., & Reeves, R. R. (1993). Distribution and movement. In: Bowhead Whales: Population and Ecology. University of Alaska Press.

- IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Balaena mysticetus.

- Matishov, G., & Belikov, S. (2019). Seasonal movements and population structure of bowhead whales in the Russian Arctic. Polar Biology, 42, 231–244.

North Atlantic Right Whale (Eubalaena glacialis)

North Atlantic Right Whales are large baleen whales inhabiting the temperate waters of the North Atlantic Ocean. Adults typically reach 13–16 meters in length and weigh up to 70,000 kilograms. They are named “right whales” because they were historically considered the “right” whales to hunt due to their slow swimming speed, buoyancy when killed, and high blubber content. These whales are critically endangered, with fewer than 350 individuals estimated to remain, making them one of the rarest large whale species in the world.

Physical Characteristics

North Atlantic Right Whales have robust, rotund bodies with no dorsal fin and a broad back. Their heads are massive, comprising approximately one-quarter of their body length, and are covered with rough patches of callosities that are unique to each individual, allowing researchers to identify whales. They possess long baleen plates, up to 3 meters, which they use to filter copepods, krill, and other small invertebrates from the water. Their skin is dark gray or black, sometimes with white patches on the belly.

Habitat and Distribution

These whales inhabit coastal and offshore waters along the eastern coast of North America and occasionally near western Europe. Key habitats include the Gulf of Maine, the southeastern United States, and the Bay of Fundy, where seasonal feeding, breeding, and calving occur. They favor areas with abundant zooplankton and shallow waters, which makes them more vulnerable to human activities.

Feeding Behavior

North Atlantic Right Whales are slow filter feeders, using their baleen plates to skim the surface or mid-water for dense patches of zooplankton. They feed primarily on copepods and krill, consuming thousands of kilograms per day during feeding seasons. Observational studies and tagging data reveal that right whales often feed while swimming slowly near the surface, a behavior that increases their risk of ship strikes.

Social Structure and Reproduction

Right Whales are generally solitary or found in small groups of 2–6 individuals, though larger aggregations form during feeding seasons. Females reach sexual maturity around 8–10 years, while males mature slightly earlier. Gestation lasts approximately 12–13 months, and females give birth to a single calf every 3–5 years. Calves measure around 4–5 meters at birth and are nursed for about a year. Strong maternal care is observed, and mother-calf pairs often remain close during early life stages.

Threats and Conservation Status

North Atlantic Right Whales face severe threats from human activity, leading to their critically endangered status:

- Ship Strikes: Collisions with large vessels are a leading cause of mortality.

- Fishing Gear Entanglement: Ropes and nets used in lobster and crab fisheries can entangle whales, causing injury or death.

- Noise Pollution: Increased shipping and industrial activity disrupts communication, navigation, and feeding.

- Climate Change: Shifts in plankton distribution affect prey availability, potentially altering migration and feeding patterns.

Conservation efforts include vessel speed restrictions, gear modifications in fisheries, and dedicated marine protected areas. Despite these measures, population recovery remains slow.

Scientific Observations

- Callosity Identification: Researchers use photographs of callosities to track individual whales and monitor population dynamics.

- Migration: Tagging studies reveal seasonal north–south migration along the U.S. East Coast, with feeding in the Gulf of Maine during summer and calving in the southeastern U.S. during winter.

- Feeding Ecology: Recent studies show prey patches are highly variable, leading to foraging adjustments and sometimes prolonged fasting periods.

- Human Impact Monitoring: Long-term monitoring demonstrates correlations between shipping lanes and injury rates, informing conservation strategies.

References

- Kraus, S. D., & Rolland, R. M. (2007). The Urban Whale: North Atlantic Right Whales at the Crossroads. Harvard University Press.

- Pettis, H. M., Hamilton, P. K., Brown, M. W., & Knowlton, A. R. (2018). North Atlantic right whale consortium 2018 annual report card. NOAA Technical Memorandum.

- Rolland, R. M., Parks, S. E., Hunt, K. E., Castellote, M., Corkeron, P. J., Nowacek, D., & Kraus, S. D. (2012). Evidence that ship noise increases stress in right whales. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 279(1737), 2363–2368.

- Pace, R. M., Corkeron, P. J., & Kraus, S. D. (2017). State–space mark–recapture estimates reveal a recent decline in abundance of North Atlantic right whales. Ecology and Evolution, 7(19), 8730–8741.

- IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Eubalaena glacialis.

Social Structures and Communication in Whales

Whale sociality ranges from solitary individuals to complex matrilineal pods. Communication is vital, with species-specific vocalizations used for navigation, foraging coordination, mating, and social bonding. Studies show cultural transmission of behaviors and vocal patterns, suggesting advanced cognitive capacities.

Key Reference:

Conclusion

Whales are incredible marine mammals whose biology and behavior continue to captivate scientists and the public alike. Their conservation remains a priority due to ongoing threats. Continued research employing acoustic monitoring, satellite tracking, and genetic analysis is essential to understanding and protecting these giants of the ocean.

Dolphins

Dolphins, members of the family Delphinidae within the order Cetacea, are among the most widely recognized and studied marine mammals. Renowned for their intelligence, complex social structures, and sophisticated communication, dolphins have fascinated scientists and the public for centuries. With over 90 species globally, ranging from the small Maui’s dolphin to the robust bottlenose dolphin, these mammals occupy diverse habitats, from coastal shallows to deep offshore waters.

Physical Characteristics and Diversity

Dolphins vary significantly in size, from the Maui’s dolphin, measuring about 1.5 meters and weighing 50 kg, to the orca, which is technically the largest member of the dolphin family, growing up to 9 meters and weighing over 6 tons. Most dolphins share a streamlined body, a pronounced beak-like snout, and a dorsal fin aiding in agile swimming. Their skin is smooth and rubbery, helping reduce drag in water.

Habitat and Distribution

Dolphins inhabit nearly all oceans and many freshwater systems worldwide. Coastal species often occupy estuaries and river mouths, while pelagic species thrive in deep offshore waters. Some species have adapted to freshwater environments, such as the Amazon river dolphin.

Behavior and Social Structure

Dolphins are among the most social animals on Earth, typically living in groups called pods. These pods exhibit cooperative hunting, social learning, and complex alliances. Dolphins possess individual personalities and can recognize themselves in mirrors, indicating high self-awareness.

Communication and Echolocation

Dolphins use advanced communication including clicks, whistles, and body language. Echolocation helps them locate prey, navigate, and avoid obstacles. Signature whistles serve as individual names, fostering social bonds.

Intelligence and Problem Solving

Dolphins exhibit remarkable cognitive abilities, including tool use and cultural transmission. For example, some bottlenose dolphins use marine sponges to protect their snouts while foraging, a learned behavior.

Reproduction and Lifespan

Dolphins can live over 40 years. Gestation lasts 10–17 months depending on species. Calves are born tail-first to avoid drowning and learn social behaviors from their mothers.

Threats and Conservation Status

- Bycatch in fishing gear

- Habitat degradation from coastal development and pollution

- Noise pollution interfering with communication

- Hunting and captivity pressures

Several species are listed as vulnerable or endangered, such as the Maui’s dolphin and vaquita.

Scientific Research and Monitoring

Satellite tracking, acoustic monitoring, and genetic analysis help understand dolphin populations and behaviors. Vocal learning studies show dolphins can imitate novel sounds.

Detailed Species Highlights

Bottlenose Dolphin (Tursiops truncatus)

The most studied species worldwide, known for curiosity and human interaction. They use cooperative hunting and complex social alliances.

Common Dolphin (Delphinus delphis)

Fast swimmers in offshore waters, forming large social groups and exhibiting energetic behaviors.

Indo-Pacific Humpback Dolphin (Sousa chinensis)

Known for its hump and pink coloration, inhabits shallow coastal waters facing threats from habitat loss.

Conclusion

Dolphins combine physical adaptations with advanced cognitive and social skills. Protecting them requires global conservation efforts and better understanding of their lives.

Further Reading and References

Manta Rays

Manta rays, belonging to the genus Manta within the family Mobulidae, are some of the most impressive and enigmatic creatures inhabiting the world’s tropical and subtropical oceans. Known for their vast size, graceful swimming, and curious nature, mantas have captivated marine biologists and ocean enthusiasts alike.

Physical Characteristics and Species

Manta rays are large, flat-bodied cartilaginous fish closely related to sharks and other rays. The two main recognized species are the reef manta ray (Manta alfredi) and the giant oceanic manta ray (Manta birostris).

- Giant Oceanic Manta Ray (Manta birostris): The larger of the two, it can reach wingspans of up to 7 meters (23 feet) and weigh as much as 1,350 kilograms (3,000 pounds). They have a broad, diamond-shaped body with triangular pectoral fins resembling wings, which they use to glide effortlessly through the water.

- Reef Manta Ray (Manta alfredi): Smaller, with wingspans up to 5.5 meters (18 feet), these mantas typically inhabit coastal reef environments.

Manta rays are characterized by their cephalic fins—two horn-shaped fins extending from the front of their heads—which help funnel plankton-rich water into their wide mouths. Their dorsal surface ranges in color from dark gray to black, often marked with distinctive white patterns unique to each individual, which scientists use for identification.

Habitat and Distribution

Manta rays are found throughout tropical, subtropical, and temperate waters globally, favoring coastal areas, coral reefs, and offshore pelagic zones. The reef manta tends to remain nearshore, often aggregating around cleaning stations where cleaner fish remove parasites from their skin. The giant oceanic manta, however, is highly migratory, traversing vast ocean distances and occasionally recorded crossing entire ocean basins.

Feeding and Behavior

Mantas are filter feeders, consuming enormous quantities of plankton and small fish by swimming with open mouths and filtering water through specialized gill rakers. Unlike many rays, mantas are pelagic and spend most of their time in open water.

Behaviorally, manta rays display remarkable intelligence and curiosity. They have been observed approaching divers and researchers, seemingly investigating their surroundings. Mantas also engage in complex social behaviors, including coordinated feeding and seasonal aggregations for mating.

Reproduction and Lifespan

Manta rays reproduce via ovoviviparity: females give birth to one or two live pups after a gestation period estimated at 12-13 months. Manta pups are relatively large at birth, measuring about 1.5 meters in wingspan.

Mantas mature slowly and have low reproductive rates, which makes their populations particularly vulnerable to human impacts. Lifespan estimates vary, but they may live up to 50 years or more in the wild.

Conservation Status and Threats

- Targeted Fishing: In some regions, manta rays are hunted for their gill plates, which are used in traditional Chinese medicine, despite lacking scientific support for medicinal properties.

- Bycatch: Accidental capture in fishing nets poses a major threat, especially in coastal areas with intensive fishing.

- Habitat Damage: Coral reef degradation and pollution affect their feeding and breeding grounds.

- Climate Change: Altered ocean temperatures and currents can impact plankton distribution, thus affecting manta feeding patterns.

Scientific Research and Observations

Researchers employ photo-identification techniques by cataloging unique spot patterns on manta bellies, enabling long-term monitoring of individuals and populations. Satellite tagging has revealed their extensive migratory behavior, sometimes covering thousands of kilometers annually.

Studies (Marshall et al., 2011) have highlighted their intelligence through observed behaviors such as somersault feeding, where mantas perform multiple loops to maximize plankton intake.

Acoustic tracking has also provided insights into their use of cleaning stations and social aggregation sites, which are critical for their health and reproduction.

Detailed Observations

- Social Behavior: Mantas show complex social dynamics, including dominance interactions during mating seasons and group feeding tactics that maximize plankton harvest efficiency.

- Cleaning Stations: Mantas visit specific reef sites where small cleaner fish remove parasites, an important behavior for maintaining skin health and hygiene.

- Curiosity and Interaction: Divers often report mantas approaching and following them, displaying apparent curiosity without aggression.

Conclusion

Manta rays are oceanic marvels combining enormous size with grace and intelligence. Their unique biological and behavioral traits make them essential contributors to marine ecosystems. Protecting mantas requires global cooperation to curb overfishing, reduce bycatch, and preserve their critical habitats. Continued scientific research will improve our understanding and guide effective conservation strategies to ensure these gentle giants thrive in our oceans.

Key Scientific References

- Marshall, A. D., & Bennett, M. B. (2010). Reproductive ecology of the reef manta ray Manta alfredi in southern Mozambique. Journal of Fish Biology, 77(5), 1149-1164.

- Marshall, A. D., et al. (2011). Morphology and molecular systematics of manta and devil rays (Chondrichthyes: Mobulidae), with an updated taxonomic arrangement for the genus Manta. Zootaxa, 2821(1), 22–30.

- Stevens, G., & Fernando, D. (2018). Manta Rays: Biology, Ecology and Conservation. CRC Press.

Seals

Seals belong to the group of marine mammals known as pinnipeds, which also includes sea lions and walruses. They are well adapted to aquatic life but maintain strong ties to terrestrial environments, where they breed, rest, and molt. There are around 33 species of seals, divided into two main families: Phocidae (true or earless seals) and Otariidae (eared seals, including sea lions and fur seals).

Physical Characteristics and Adaptations

Seals have streamlined bodies covered with a thick layer of blubber that insulates them against cold ocean waters. Their limbs have evolved into flippers—foreflippers for maneuvering and hind flippers for propulsion. True seals (Phocidae) lack external ear flaps and move on land by wriggling on their bellies, whereas eared seals have visible external ears and can “walk” on land using their flippers.

Habitat and Distribution

Seals are found in nearly every ocean, from the icy waters of the Arctic and Antarctic to temperate and tropical seas. For example, the harbor seal (Phoca vitulina) inhabits coastal areas of the Northern Hemisphere, while the elephant seal (Mirounga spp.) breeds on remote southern ocean islands.

Feeding Behavior and Diet

- Opportunistic feeders consuming a wide variety of prey depending on availability.

- Elephant seals perform deep, prolonged dives exceeding 1500 meters in search of squid and deep-sea fish.

- Harbor seals typically feed in shallow waters and estuaries on schooling fish and invertebrates.

Social Structure and Reproduction

Seals exhibit diverse social behaviors: many species form large breeding colonies during mating seasons where males establish territories and compete for females. True seals tend to be more solitary outside breeding seasons, whereas eared seals often form large, socially complex groups. Reproductive strategies include delayed implantation, allowing females to time birth with favorable environmental conditions. Pups are typically nursed for several weeks to months, during which mothers fast on land while providing nutrient-rich milk.

Conservation Status and Human Impact

Several seal species face threats due to habitat loss, pollution, climate change, and historical overhunting. Some populations, such as the Mediterranean monk seal (Monachus monachus), are critically endangered. Human activities affecting seals include bycatch in fishing gear, oil spills, and climate change reducing ice habitats critical for breeding in Arctic species like the ringed seal (Pusa hispida). Conservation efforts include protected marine areas, regulations on hunting, and rehabilitation programs for injured individuals.

Scientific Research and Observations

Recent studies using satellite tagging have revealed extensive migratory patterns and habitat use in species like the gray seal (Halichoerus grypus). Observations show that seals can exhibit complex behaviors such as cooperative hunting and vocal communication, particularly during breeding seasons. Physiological studies demonstrate their remarkable adaptations for diving, including tolerance to hypoxia and efficient oxygen storage. Behavioral research also notes seals’ ability to learn and respond to environmental changes, indicating higher cognitive functions than previously assumed.

Detailed Observations

- Diving Ability: Elephant seals can hold their breath for over 100 minutes and dive to depths exceeding 1500 meters, making them among the deepest-diving mammals.

- Social Behavior: Male seals often engage in intense vocal and physical competitions for harems during breeding seasons. For example, male harbor seals produce underwater vocalizations to establish dominance.

- Communication: Seals use vocalizations, body postures, and even slapping the water surface to communicate, especially mothers and pups.

- Human Interactions: Seals generally avoid humans but can become habituated in areas with frequent human presence, sometimes leading to conflicts.

Key Scientific References

- Kovacs, K. M., et al. (2011). Impacts of changing sea-ice conditions on Arctic marine mammals.

- McMahon, C. R., et al. (2003). Diving behaviour of southern elephant seals.

- Bowen, W. D., & Iverson, S. J. (2013). Methods of estimating marine mammal diet and applications to the diet of seals.

- Hammill, M. O., & Smith, T. G. (1991). The diving behaviour of ringed seals.

- Boyd, I. L., & Croxall, J. P. (1996). Dive duration and post-dive surface behaviour in the Antarctic fur seal.

Penguins

Penguins are a unique group of flightless seabirds belonging to the family Spheniscidae. Unlike most birds, penguins have adapted to an aquatic lifestyle, relying on their powerful flippers for swimming rather than wings for flying. There are currently 18 recognized species of penguins, all native to the Southern Hemisphere, primarily concentrated in Antarctica, sub-Antarctic islands, and temperate coastal regions of South America, Africa, Australia, and New Zealand.

Physical Characteristics and Adaptations

Penguins are characterized by their robust, streamlined bodies covered in dense waterproof feathers that provide insulation against cold temperatures. Their wings have evolved into rigid flippers optimized for efficient underwater propulsion. The body shape minimizes drag, allowing penguins to reach impressive swimming speeds, often between 6 to 15 km/h depending on the species.

Their eyes are adapted for underwater vision, and they possess excellent depth perception which aids in hunting prey. Penguins’ legs are set far back on their bodies, which assists in their distinctive upright posture on land but results in a waddling gait.

Habitat and Distribution

Penguins occupy a range of habitats in the Southern Hemisphere. The Emperor penguin (Aptenodytes forsteri), the largest species, is endemic to Antarctica, enduring the harshest winters by breeding on sea ice. The Galápagos penguin (Spheniscus mendiculus) is unique as the only species living north of the equator, inhabiting the warm waters of the Galápagos Islands.

Other species such as the King penguin (Aptenodytes patagonicus), Adélie penguin (Pygoscelis adeliae), and Magellanic penguin (Spheniscus magellanicus) are distributed across sub-Antarctic islands and temperate coastlines.

Feeding Behavior and Diet

- Penguins are carnivorous and primarily consume fish, krill, squid, and other small marine organisms.

- Emperor penguins undertake long and deep dives exceeding 500 meters to catch prey during the Antarctic winter.

- Smaller species such as the Little Blue penguin (Eudyptula minor) hunt in coastal waters, feeding mostly on small fish and crustaceans.

- Penguins exhibit remarkable diving endurance and speed, supported by physiological adaptations such as increased oxygen storage in blood and muscles.

Social Structure and Reproduction

- Penguins are social birds that often form large breeding colonies known as rookeries, sometimes numbering in the tens of thousands.

- Emperor penguins breed during the Antarctic winter; males incubate a single egg on their feet under a brood pouch while females forage at sea.

- Most species lay two eggs per breeding season, with incubation shared between parents.

- Chicks are typically cared for by both parents and often form crèches (groups of young) for warmth and protection.

Mating behaviors include vocalizations and displays that help pairs recognize each other in large colonies.

Conservation Status and Human Impact

- Several penguin species face conservation challenges due to climate change, overfishing, habitat disturbance, and pollution.

- Melting sea ice affects species like the Emperor and Adélie penguins by reducing breeding habitat and altering prey availability.

- Overfishing reduces the abundance of prey such as krill and fish, impacting penguin food sources.

- Oil spills and marine pollution can cause direct mortality and degrade habitat quality.

Conservation measures include marine protected areas, fisheries management, and monitoring of populations to inform adaptive conservation strategies.

Scientific Research and Observations

Satellite tracking and time-depth recorders have greatly advanced knowledge of penguin foraging ranges, diving behavior, and migration routes. Research highlights penguins’ remarkable physiological adaptations to cold and diving, as well as their complex social behaviors in breeding colonies.

Studies also emphasize the impact of environmental changes on penguin populations, making them valuable indicators of ecosystem health.

Detailed Observations

- Diving Capacity: Emperor penguins can dive over 500 meters and remain underwater for more than 20 minutes, showcasing exceptional physiological adaptation.

- Social Behavior: Vocalizations are species-specific and crucial for mate and chick recognition within noisy, crowded colonies.

- Communication: Penguins use a combination of calls, postures, and bill tapping to communicate, especially between mates and parents with chicks.

- Human Interactions: While generally not aggressive, penguins are vulnerable to human disturbance; tourism and research activities require careful management to minimize stress.

Key Scientific References

- Williams, T. D. (1995). The Penguins: Spheniscidae. Oxford University Press.

- Ainley, D. G., Russell, J., Jenouvrier, S., et al. (2010). Antarctic penguin response to habitat change as Earth’s troposphere reaches 2°C above preindustrial levels. Ecological Monographs.

- Kooyman, G. L. (2002). Diving Physiology of Marine Mammals and Seabirds. Cambridge University Press.

- Lynch, H. J., LaRue, M. A., Fagan, W. F., et al. (2012). Inhabited islands and breeding localities of the world’s penguins. Diversity and Distributions.

- Trathan, P. N., García-Borboroglu, P., Boersma, D., et al. (2015). Pollution, habitat loss, fishing, and climate change as critical threats to penguins. Conservation Biology.

Stingrays

Stingrays are a diverse group of cartilaginous fishes belonging to the order Myliobatiformes within the subclass Elasmobranchii, which also includes sharks and skates. With over 200 species described, stingrays are closely related to sharks but exhibit a distinctive flattened body shape adapted for benthic (seafloor) living. They inhabit marine and some freshwater environments worldwide, ranging from shallow coastal waters and estuaries to deep ocean floors.

Physical Characteristics and Morphology

Stingrays have a characteristic flattened, disc-like body with broad pectoral fins fused to the head and trunk, enabling them to glide gracefully over the seafloor. Their size varies greatly; some species measure less than 30 cm in disc width, while others, such as the giant oceanic manta ray (Mobula birostris), can reach widths of up to 7 meters.

Their tails are slender and whip-like, often equipped with one or more venomous barbed spines used for defense. The dorsal surface of stingrays is usually covered with rough, textured skin, while the ventral side is smooth and pale. Eyes are positioned dorsally, while the mouth and gill slits are located on the ventral surface, adapted for bottom feeding.

Habitat and Distribution

Stingrays are widely distributed across tropical and temperate oceans globally. Many species inhabit shallow coastal habitats like coral reefs, sandy bottoms, and seagrass beds, while others are found in deeper waters. Some species, such as the freshwater river stingrays (Potamotrygonidae family), are adapted to freshwater rivers and lakes in South America.

Feeding Behavior and Diet

Stingrays are mostly benthic feeders, using their flattened bodies to camouflage against the seafloor as they hunt for prey. Their diet consists primarily of mollusks, crustaceans, small fish, and worms.

They use specialized, pavement-like teeth to crush hard shells of prey. Stingrays locate food using electroreception, detecting weak electrical signals emitted by buried animals. They often employ a suction feeding mechanism, sucking prey from the substrate.

Reproduction and Life Cycle

Most stingrays are ovoviviparous, meaning embryos develop inside eggs retained within the mother’s body, and live young are born. Gestation periods vary but typically last several months. Litter sizes can range from one to several pups depending on species.

Parental care after birth is minimal, and juveniles are independent from birth. Sexual maturity is reached at different ages depending on species and environmental conditions.

Conservation Status and Threats

Stingrays face several threats due to human activity. Overfishing and bycatch in commercial fisheries significantly reduce their populations, particularly as their slow growth and low reproductive rates limit recovery.

Habitat degradation, including destruction of coral reefs and seagrass beds, affects stingray nursery and feeding grounds. Additionally, pollution and coastal development further threaten their habitats.

Although some species are listed as Least Concern, many others are Vulnerable or Endangered according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

Scientific Research and Observations

- Electroreception: Stingrays possess ampullae of Lorenzini, specialized sensory organs that detect electrical fields produced by prey, even when buried under sand.

- Camouflage and Behavior: Their dorsoventrally flattened bodies and coloration provide excellent camouflage, allowing them to avoid predators and ambush prey.

- Defense Mechanism: The venomous barb can inflict painful wounds, used mainly for defense rather than hunting.

- Social Behavior: While many stingrays are solitary, some species aggregate seasonally for mating or feeding.

Key Scientific References

- Last, P. R., & Stevens, J. D. (2009). Sharks and Rays of Australia (2nd ed.). CSIRO Publishing.

- Kyne, P. M., & Simpfendorfer, C. A. (2010). Deepwater Chondrichthyans. In J. C. Carrier, J. A. Musick, & M. R. Heithaus (Eds.), Biology of Sharks and Their Relatives (pp. 37–114). CRC Press.

- Macesic, L. J., & Kajiura, S. M. (2010). The function of the stingray tail spine: An experimental approach. Journal of Experimental Biology, 213(11), 1905–1911.

- Marshall, A. D., & Bennett, M. B. (2010). Reproductive ecology of stingrays. Environmental Biology of Fishes, 90(3), 273–288.

- Dulvy, N. K., Fowler, S. L., Musick, J. A., et al. (2014). Extinction risk and conservation of the world’s sharks and rays. eLife, 3, e00590.

Polar Bears

Polar bears (Ursus maritimus) are large carnivorous mammals uniquely adapted to the harsh Arctic environment. They are the largest land carnivores, closely related to brown bears but highly specialized for life on sea ice. Polar bears have evolved over hundreds of thousands of years to thrive in the extreme cold, relying heavily on sea ice as a platform for hunting their primary prey, seals.

Physical Characteristics and Adaptations

Polar bears possess thick insulating fur and a dense layer of subcutaneous fat that provide exceptional thermal insulation against Arctic cold. Their fur appears white, helping camouflage them in snowy and icy surroundings, but is actually translucent. Their large, powerful limbs and broad paws distribute weight when walking on thin ice and assist in swimming, enabling them to cover long distances in search of food.

Polar bears have sharp claws and strong jaws adapted for hunting seals. Their keen sense of smell allows them to detect prey nearly a kilometer away and beneath several feet of compacted snow.

Habitat and Distribution

Polar bears are native to the circumpolar Arctic region, found in areas of Canada, Greenland, Norway (Svalbard), Russia, and the United States (Alaska). They spend much of their life on the sea ice of the Arctic Ocean and adjacent seas. Seasonal sea ice fluctuations largely determine their range and hunting opportunities.

Feeding and Behavior

Polar bears are apex predators specializing in hunting seals, particularly ringed seals (Pusa hispida) and bearded seals (Erignathus barbatus). They use stealth and patience to stalk seals resting on ice or waiting at breathing holes. When hunting is not possible, polar bears may scavenge carcasses or consume vegetation, though these are minor parts of their diet.

Polar bears are largely solitary animals but may gather in areas with abundant food, such as seal pupping sites. They are excellent swimmers and can sustain long-distance swims, which helps them navigate fragmented sea ice.

Reproduction and Life Cycle

Polar bears mate in the spring, with females giving birth in winter dens dug in snowdrifts on land or stable sea ice. Cubs are born blind and helpless, typically two per litter. Mothers nurse and protect cubs for about two and a half years, teaching them survival skills before independence.

Females reach sexual maturity around 4-6 years of age, and polar bears can live up to 25-30 years in the wild.

Conservation Status and Threats

Polar bears are classified as Vulnerable by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) due to ongoing habitat loss caused by climate change. The rapid decline in Arctic sea ice reduces their hunting grounds and access to prey, threatening their survival.

Additional threats include pollution, oil and gas exploration, and increased human-bear conflicts as bears spend more time on land. Conservation efforts focus on mitigating climate change, protecting critical habitat, and managing human-bear interactions.

Scientific Research and Observations

- Thermoregulation: Polar bears maintain body heat with a unique combination of fur and fat, while also possessing black skin underneath to absorb solar radiation.

- Swimming Ability: They can swim continuously for hours, covering over 100 kilometers, using their large forepaws as paddles.

- Behavioral Flexibility: Some polar bears have adapted to changing ice conditions by altering hunting strategies and foraging on alternative food sources.

- Human Interaction: Polar bear encounters with humans are increasing as sea ice retreats; safety protocols and community education are crucial.

Key Scientific References

- Amstrup, S. C., Marcot, B. G., & Douglas, D. C. (2008). A Bayesian network modeling approach to forecasting the 21st century worldwide status of polar bears. Ecological Monographs, 78(2), 257–276.

- Durner, G. M., Amstrup, S. C., & Ambrosius, K. J. (2001). Remote identification of polar bear maternal den habitat in northern Alaska. Arctic, 54(2), 115–121.

- Stirling, I., & Derocher, A. E. (2012). Effects of climate warming on polar bears: A review of the evidence. Global Change Biology, 18(9), 2694–2706.

- Laidre, K. L., Stirling, I., & Lowry, L. F. (2015). Quantifying the sensitivity of Arctic marine mammals to climate-induced habitat change. Ecological Applications, 18(sp2), S97–S125.

- Wiig, Ø., Derocher, A. E., & Bangjord, G. (2008). Polar bear conservation status in Norway and globally. Polar Biology, 31(8), 889–899.

Social Behavior and Sensory Communication in Sharks

Although sharks are often perceived as solitary hunters, many species exhibit complex social behaviors including schooling, territoriality, and hierarchical interactions. Sharks rely on electroreception, olfaction, and lateral line systems for navigation and prey detection. Recent studies suggest some species may use body language and chemical cues for intra-species communication.

Key Reference: